The biomass is the “workforce" of a waste treatment system. In a dynamic state of flux, different microbes are dying while others grow and become more dominant. Under adverse conditions such as toxic shock, certain bacterial populations may be reduced or eliminated, causing poor effluent quality. Examples of toxic shock would be black liquor spills in paper mills or a process upset in a chemical plant sending high levels of terpenes to the wastewater plant.

Historically, under such conditions, waste treatment plants have been slow to recover. National Pollution Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permits often have been violated or the manufacturing process stopped to avoid the legal repercussions of NPDES permit violations.

The biological additives industry was started in the early 1960’s to address the problems of slow biomass recovery and to supplement lost bacterial populations. The application of this technology is termed bioaugmentation.

Defining the Terms

Frequently, the terms bioremediation and bioaugmentation are used interchangeably. Bioremediation will be defined here as the use of selected microorganisms to accomplish a biological cleanup of a specified contaminated area, such as soil or water; bioaugmentation will be defined as the application of selected microorganisms to enhance the microbial populations of an operating waste treatment facility to improve water quality or lower operating costs. In other words, bioremediation deals with a finite project or area, while bioaugmentation involves working to improve a continuous process.

Bioaugmentation has been practiced since the early 1960s. Because of frequent misapplication of additives or poor documentation of results, the technology has been regarded as less than scientific.

A prevailing belief has been that, over time, the proper microbes will populate the system and become acclimated to the influent. This approach assumes that the indigenous population introduced via routes such as windblown solids, rain water and the plant influent stream always will contain the best suited organisms.

In reality, even though the natural population may develop into an acceptable

one, there may be performance limitations that only can be overcome through

the induction of superior strains of microorganisms.

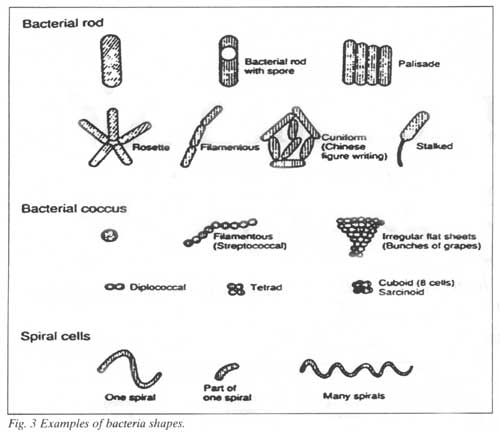

In the aeration basin of a typical industrial

waste treatment plant, one should expect to find numerous species or strains

of bacteria. This bacterial diversity, as it is called, is necessary because

some types of bacteria degrade different compounds more effectively and

efficiently.

These bacteria generally are well suited

to handle the contaminants in the waste influent and will become acclimated,

over time, to provide the desired results, assuming a steady state of

operation is approximated. Unfortunately, few industrial waste treatment

plants ever achieve steady state. The influent characteristics may change

drastically from week to week, or even day to day.

These variations may be due to production schedules

of batch processes, chemical spills in the production plant, or incapable

plant equipment. Many treatment plant biological populations never attain

optimum numbers or diversity of species.

Without bioaugmentation, the indigenous

population should consist of numerous types of organisms. Some of these

organisms are more efficient and effective than others at degrading the

various compounds and producing a settleable biomass. Figure 4 simplistically

categorizes the biomass into Population A (desired indigenous organisms),

and Population C (selected bioaugmentation organisms). The goal of the

bioaugmentation program is to enhance the growth of Population A, establish

the selected organisms of Population C, and minimize Population B.

There is the question of why bioaugmentation products

must be fed continuously after the initial dosing of product. Due to system

upsets and influent composition changes, a maintenance dosage is required

to maintain the desired population diversity.

Proper monitoring of the system using statistical

process control, combined with microbiological analysis techniques, will

provide the information that the bioaugmentation consultant needs to maintain

the desired population. By using microscopic analysis and advanced plating

techniques, the consultant can correlate bacterial population characteristics

with plant performance for a particular waste treatment system. Because

every system is unique, the optimum population will vary from plant to

plant.

Reprinted from Environmental Protection, October 1992